|

| Myles Keogh Fighting Celt 1840 - 1876 |

After recently visiting the eerie Battlefield of Little Big Horn in Eastern Montana I was reminded again of the life of Myles Keogh. We devote a chapter to this son of Erin in our forthcoming work 101 Fighting Celts: From Boudicca to MacArthur...

Myles Keogh

Many myles traveled

battles fought. Little Bighorn

one too many.

Myles Keogh, born in 1840 to a farming family in

Leighlinbridge,

County Carlow, Ireland, would lead a life of swashbuckling adventure. Keogh

would leave Ireland to serve in the Papal Army, would fight at Gettysburg in

the Union Army, and would be killed as an officer with Custer’s 7th Cavalry at

the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June 1876.

Stalin once famously asked, “How many divisions

does the Pope of Rome have?” In 1870, Rome was invaded by an Italian Army, the Papal

States were incorporated into the Italian state (except for Vatican City), and

the Papal Army was disbanded. But in 1860, the pope still did have divisions and a small army that was tasked with defending

the territory of the papal states. That year saw a watershed moment during the

Risorgimento—the struggle for Italian nationhood. In 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi,

Italian general and nationalist, landed on the coast of Sicily with his famous

Mille [thousand] Redshirts, who would wrest control of the island from the

Bourbons on behalf of a unified Italy.

|

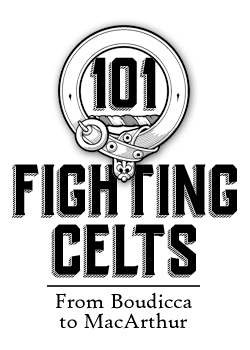

| St. Patrick's Battalion Kneeling in Green Papal Guard |

It was also in 1860 that twenty-year-old Keogh

left Ireland for Italy, where he enlisted as a second lieutenant in the St.

Patrick’s Battalion of the Papal Guard. Keogh was present at the Battle of

Castelfidardo on September 18, 1860, where Italian forces defeated the Papal

Army, which they outnumbered by a factor of four to one. This battle was really

more of a skirmish, which saw less than a hundred soldiers killed on either

side. Keogh did earn a medal for his service to the pope—the impressively named

Cross of the Order of St. Gregory the Great. Keogh then served in the Irish

Papal Zouaves in Rome and was recruited for the Union Army by John Hughes, the

Archbishop of New York, on his 1862 visit to the Vatican. Hughes was working on

behalf of Secretary of State William Seward at the time.

Arriving in New York City on April 1, 1862,

Keogh was enlisted as a captain in the Union Army. He served as aide de camp to

General James Shields (born in Tyrone, Ireland) in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

Shields told his Irish soldiers, “You fight in a sacred cause. Two worlds are watching you.” Keogh was then transferred to serve briefly in

the staff of another officer of Celtic descent, George McClellan. Little Mac

described Keogh as “a most

gentlemanlike man, of soldierly appearance.”

Keogh then moved on to serve in the headquarters

of cavalry brigadier general John Buford. Keogh saw action at some of the most

famous battles of the American Civil War. He fought at Antietam, the bloodiest

single day in American military history; and he fought at Gettysburg, where

Buford distinguished himself when his cavalry patrols spotted Lee’s invasion of

Pennsylvania and he selected Gettysburg as a suitable battle site.

After Buford’s premature death from typhoid in

December 1863 at the age of thirty-seven, Keogh was transferred to the staff of

General George Stoneman. Once more. Keogh was in the thick of the action.

Stoneman was charged by General Sherman to lead a raid that would attempt to

rescue thousands of Union POWs imprisoned at Andersonville in Georgia. At the

battle of Sunshine Church in Macon, Georgia, Stoneman was defeated by a

Confederate force. Both Stoneman and Keogh were captured, though they were released

a few months later as part of a prisoner exchange. On April 12, 1865, three

days after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Keogh was still fighting. That day he

led the 11th Kentucky Cavalry in their assault on Salisbury, North Carolina, ultimately

capturing fourteen guns and a thousand Confederate troops.

Having participated in over thirty Civil War

engagements, Keogh finished the war as a brevetted major and lieutenant

colonel. The demobilization that followed the conclusion of the war resulted in

massive downgrades in terms of military rank. Keogh would serve as a captain in

the 7th Cavalry with Lieutenant Colonel Custer in the 1876 Sioux campaign.

Custer’s 7th Cavalry had a distinctively Celtic

nature. They famously rode into battle on the western frontier to the tune of

an old Irish drinking song, “Garryowen.” Thomas Moore, an Irish poet, wrote the

lyrics in 1807.

Let Bacchus' sons be not

dismayed

But join with me each jovial blade

Come booze and sing and lend your aid

To help me with the chorus

Instead of spa we'll drink brown ale

And pay the reckoning on the nail

For debt no man shall go to gaol [jail]

From Garryowen in glory

But join with me each jovial blade

Come booze and sing and lend your aid

To help me with the chorus

Instead of spa we'll drink brown ale

And pay the reckoning on the nail

For debt no man shall go to gaol [jail]

From Garryowen in glory

|

| George Armstrong Custer Statue Monroe, Michigan |

In a letter dated March 5, 1876, Private Thomas

Hagan, also a 7th Cavalry trooper from Ireland, wrote a poignant and prophetic

letter to his sister:

We are to start the 10th

of this month for the Big Horn country. The Indians are getting bad again. i [sic] think that we will have some hard

times again this summer. The old chief Sitting Bull says that he will not make

peace with the whites as long as he has a man to fight … As soon as i [sic] got back of the campaign i [sic] will rite [sic] you. That is if I do

not get my hair lifted by some Indian.

From your loving

brother,

T.P. Eagan [sic][1]

T.P. Eagan [sic][1]

Poor private Hagan would be among the 268

soldiers and officers of the US Army killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn

on June 25, 1876. The adventures of Myles Keogh would end that day as he was

killed leading Company I in a hopeless battle against perhaps as many as 2,500

Sioux warriors.

An astonishing number of those killed were of

Celtic origin. Thirteen percent of those who fell at the Little Bighorn had

been born in Celtic countries (thirty-two Ireland, two Scotland, and one Wales),

while many more were clearly of Celtic origin.[2]

|

| Custer's Last Fight |

The US military saluted the life of Myles Keogh

by naming Fort Keogh on the Yellowstone River in Montana in his honor. Anheuser-Busch

transformed Custer’s defeat at Little Bighorn into an ad campaign, commissioning

a painting titled Custer’s Last Fight and

printing posters advertising Anheuser-Busch

that adorned thousands of saloons across America. A fitting tribute to

Bacchus’ thirsty Celtic sons!

Myles Keogh is buried at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, New York.

Myles Keogh is buried at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, New York.

The legacy of Celtic fighters in the US Army

endures to this day with the 7th Cavalry, now garrisoned at Fort Hood, Texas,

which retains “Garryowen” as its official song and its nickname.

[1]

Ronald H. Nichols and Daniel I. Bird, eds., Men With Custer: Biographies of the

7th Cavalry, (Hardin

MT: Custer Battlefield Historical & Museum Association, Inc., 2010), 157.

[2]

Based on calculations from data within Nichols and Bird’s Men With Custer: Biographies of the 7th Cavalry.

Coming soon from the authors of America Invaded is 101 Fighting Celts: From Boudicca to MacArthur...

You can find signed copies of our books at

these web sites...

Or regular copies on Amazon...

Or on Kindle...

Listen to my interview with Bob Cudmore...http://bobcudmore.com/thehistorians/tracks/ChristopherKelly(August2017)(29)(mp3).mp3

And my interview...www.thebook-club.com/blog/bookshelf-interview-with-christopher-kelly

And my most recent interview...http://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2018/08/17/america-invaded-christopher-kelly