|

| Trip Advisor Review, Circa 1933 |

Prior to serving in the Republican forces during the Spanish Civil war, George Orwell worked as a plongeur or dishwasher in Paris. He also wandered England as a homeless tramp staying in doss-houses. George Orwell transformed these experiences into the book Down and Out in Paris and London (www.amzn.com/B002UDFNNO) which was published during the great Depression in 1933. This was, to say the least, an unusual path for an "old Eton boy" to take.

Nietzsche once wrote, "Poets are shameless with their experiences: they exploit them." Orwell did not hesitate to exploit his experiences as a "plongeur" in Paris or a tramp in England.

If Trip Advisor Had been around in 1933 Orwell might have posted a review something like this: "Avoid all restaurants and hotels in Paris and beyond! The sanitary conditions are appalling. There is filth on the kitchen floors. Rats infest every kitchen. The staff could care less about their customers. How many Stars? Zero!"

|

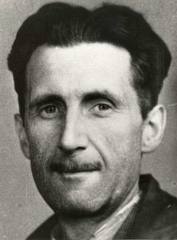

| George Orwell 1903 -1950 |

Orwell then moved on to work at a restaurant in Paris called the Auberge de Jehan Cottard as a plongeur or dishwasher. He wrote about his employer, "The Auberge was not the ordinary cheap eating-house frequented by students and workmen. We did not provide an adequate meal at less than twenty-five francs, and we were picturesque and artistic, which sent up our social standing. There were indecent pictures in the bar, and the Norman decorations--sham beams on the walls, electric lights done up as candlesticks, "peasant" pottery, even a mounting-block at the door--and the patron and the head Waiter were Russian officers, and many of the customers titled Russian refugees. In short, we were decidedly chic.

Nevertheless, the conditions behind the kitchen door were suitable for a a pigsty. For this is what our service arrangements were like.

The kitchen measured fifteen feet long by eight broad, and half this space was taken up by the stoves and tables. All the pots had to kept on shelves out of reach and there was only room for one dustbin. This dustbin used to be crammed full by midday, and the floor normally an inch deep in compost of trampled food...

There was no larder. Our substitute for one was a half-roof shed in the yard, with a tree growing in the middle of it. The meat, vegetables and so forth lay there on the bare earth, raided by rats and cats."

One of Orwell's colleague at the Auberge was a waiter named Jules. Orwell confides that 'Jules took a positive pleasure in seeing things dirty. In the afternoon, when he had not much to do, he used to stand in the kitchen doorway jeering at us for working too hard: 'Fool! Why do you wash that plate? Wipe it on your trousers. Who cares about the customers? They don't know what's going on. What is restaurant work? You are carving a chicken and it falls on the floor. You apologize, you bow, and you go out; and in five minutes you come back by another door--with the same chicken. That is restaurant work."

Has the restaurant world really changed much since 1933? One can certainly hope so, but there are many parts of the world where restaurant sanitation standards are little improved from the Paris of 1933.

Orwell then moved on to England where he tramped about the country moving from flop house to flop house. He survives on a "cuppa" and two slices with a bit of margarine. He is nearly molested at night by "Nancy" boys. He and other tramps are preached to by religious do-gooders and Salvation Army warriors.

He offers one piece of advice which is as sound for today's London as it was in 1933. Handbills were distributed on the streets of London by local merchants then as they are now. Orwell writes, "When you see a man distributing handbill you can do him a good turn by taking one, for he goes off duty when he has distributed all his bills."

Orwell writes with genuine understanding, sympathy and, often, humor in his descriptions of the grinding poverty of the working classes and those unfortunates who are unemployed and homeless. His account helps us to appreciate how fascism was able to exploit the suffering of so many throughout Europe during the Great Depression.

Commander Kelly says "Check out George Orwell's Down and Out in Paris and London. You may never think of restaurants and hotels in the same way again. Has George Orwell's review been helpful to you?"

No comments:

Post a Comment